When my sister was in high school, she went on an Urban Experience. As a lesson about homelessness, she and her classmates were challenged to spend the night in downtown Denver with only five dollars in their pockets. They would have to sleep on heat vents or in homeless shelters; they’d have to know what it’s like to be hungry; they’d emerge from it chastened and humbled and wiser for the experience.

It was fun, my sister told me.

I suppose this was the drawback: there was nothing at stake. They only had to make it for a few hours, and by morning, they’d be back in bed, well-fed and warm. In other words, it was an early opportunity for my sister to spend an entire night out. As it was, by the time I got to high school, I had already planned how I would have spent my night, but the program didn’t exist anymore.

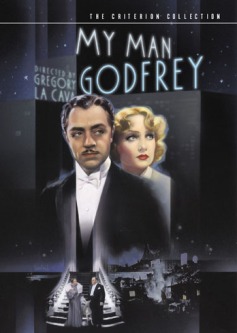

Years of city living has inured me to the homeless. I mistrust the men—and it’s almost always men, Caucasian—who linger on the devil’s strip near busy stoplights, where the traffic can back up a block’s length. Their clothes are dirty and sufficiently worn, though still serviceable, and they bear stubble on their face as proof of hardship. They hold cardboard squares with their lives’ misery condensed in black Magic Marker: got laid-off, Vietnam vet, foreclosed home, hungry family, God bless. They rarely speak. But they strike me the way William Powell strikes me in My Man Godfrey: There’s no way he could be homeless.

I wasn’t always so cynical. One evening when I was still in college, I was with my friend C___ and his boyfriend J___, hanging out in the gay neighborhood of Baltimore, Mount Vernon. We were all too young to go to the bars and clubs, but we were there to steep in the general atmosphere, reveling, as we were, in the then-new excitement of our community. We were at the base of the hill the rises towards the George Washington Monument, outside of The Buttery, a diner that would have been more aptly named “The Greasery.”

An African-American woman came up to us. She spun out her story—she needed milk for her baby at home, stuck in the city without bus fare. C___ and I, both still new to Baltimore, looked at each other, unsure of what to do. We could deal with homelessness when it was huddled in a corner, but never had it come up to confront us. As college students, we hardly had any money ourselves, though we must have had a few bucks between the two of us. We sputtered out our excuses, but she pressed on. My baby’s hungry, she insisted.

J____, from nearby Ellicott City, was getting more upset at us for engaging with her than with her for coming to us.

Finally, fed up, he gave her a few dollars. “Here,” he said. “Take it.”

When she left, she seemed to skip, with what might have been glee. “She seems happy,” I said.

“Why wouldn’t she be?” J___ replied. “She got her money.”